Warranty Cost Analysis

Statistical analysis and predictive modeling of warranty claims for a major global automotive parts manufacturer

This writeup covers a project for a major, global commercial vehicle manufacturer analyzing parts failures and warranty claims. The firm wanted to analyze its warranty claim data to identify current failure patterns, predict future failure patterns, and support corrective business policies. The project involved substantial elements of data collection, data cleaning and preparation, exploratory data analysis, data visualization, and predictive modeling. The end results included: (1) clarity on the sources and nature of data that the firm had available as well as an understanding of what further data are necessary for future business analytics development (2) versatile data visualization tools, including an interactive dashboard, for understanding warranty claim patterns and (3) predictive modeling frameworks for understanding and forecasting key metrics such as raw batch failure rates and cumulative failure percentages.

Here the aim is to distill major takeaways from two important steps in this project: data collection/preparation and predictive modeling of cumulative failures.

Data Collection & Preparation

In many data science projects, data collection and preparation are the most time-consuming steps. This project was no exception. Among the challenges encountered during this phase:

- data fragmentation: different parts of the data were housed in different company divisions and/or clients

- data formatting inconsistency: inconsistent formatting of data fields in data from different sources

- data value inconsistency: data values in some data sets were inconsistent with purported values in other data sets

- data incongruency: certain aspects of the data were incongruent with stated business practices (e.g. service times far in excess of warranty period time), raising questions of error or exceptions

- missing data: some data values were missing in a given data set; some values were present in one data but absent from another (where they should also appear)

- unstandardized data: some data fields were not standardized, resulting in multiple spellings/representations of the same values

While these issues can be worked through and resolved, this typically uses a fair amount of work. The process requires a constant back and forth between the business leaders with direct domain insight and the analysts and data scientists working the data. Some foresight, planning, and data engineering can make the data collection and preparation steps far less time-consuming. Among suggestions were:

- standardization: standardization of data (standard values, spellings, etc.), standardization of data storage formatting

- automation: automated data entry to reduce errors, misspellings, missing values

- integrated information systems: integrating information systems across different departments and even with clients to unify data sources

- problem definition: define the problem at hand in clear and direct terms

Proper implementation of these principles during data entry and storage greatly improves the ease and efficiency of data collection and the reduces the steps and resources necessary for data prep. The fourth suggestion is a critical principle that is key to the success of any analytics project. Good problem definition makes it clear what data is needed and what modeling frameworks might be worth exploring. Data projects are only valuable insofar as they are in line with an organization’s objectives.

Although many suggestions for improvements to future data collection projects were made, the firm was already aware of some of these shortcomings. They had already implemented more automated data collection and more stringent standardization while actively working toward more data integration across the firm and with clients. This project reinforced the firm’s needs and elucidated where savings in resources spent on data prep were to be found.

Weibull Modeling of Component Failures

The Weibull distribution is an extreme value distribution. Its importance to extreme value theory comes from the Fisher-Tippett-Gnedenko theorem. At a high level, the theorem says that if the distribution of the maxima (or minima) of a sequence of iid (independent and identically distributed) random variables converges to a distribution, it must be either a Weibull, a Gumbel, or a Frechet distribution. In a nutshell, it is like a central limit theorem for extreme values of samples.

The application to failure modeling comes from the observation that many component failures are the result of extreme events (e.g., the brake pad with greatest wear is likely to give out earliest). Hence extreme value distributions are prime candidates. There are some cases where the Frechet and Gumbel distributions are better suited. This depends on the tail index of the input distributions that are converging in extreme value. A detailed discussion is avoided here, see, for example, (Stupfler 2016). The Weibull is generally the favored distribution when tails are lighter. However, the Weibull can accommodate a range of tail thickness through its shape parameter \(k\). When \(k>1\), the Weibull distribution has subexponential tails. When \(k<1\) the tails are thicker than that of an exponential distribution. When \(k=1\) its tails are exponential. In fact, when \(k=1\) the distribution reduces to an exponential distribution. The probability density function for the Weibull is:

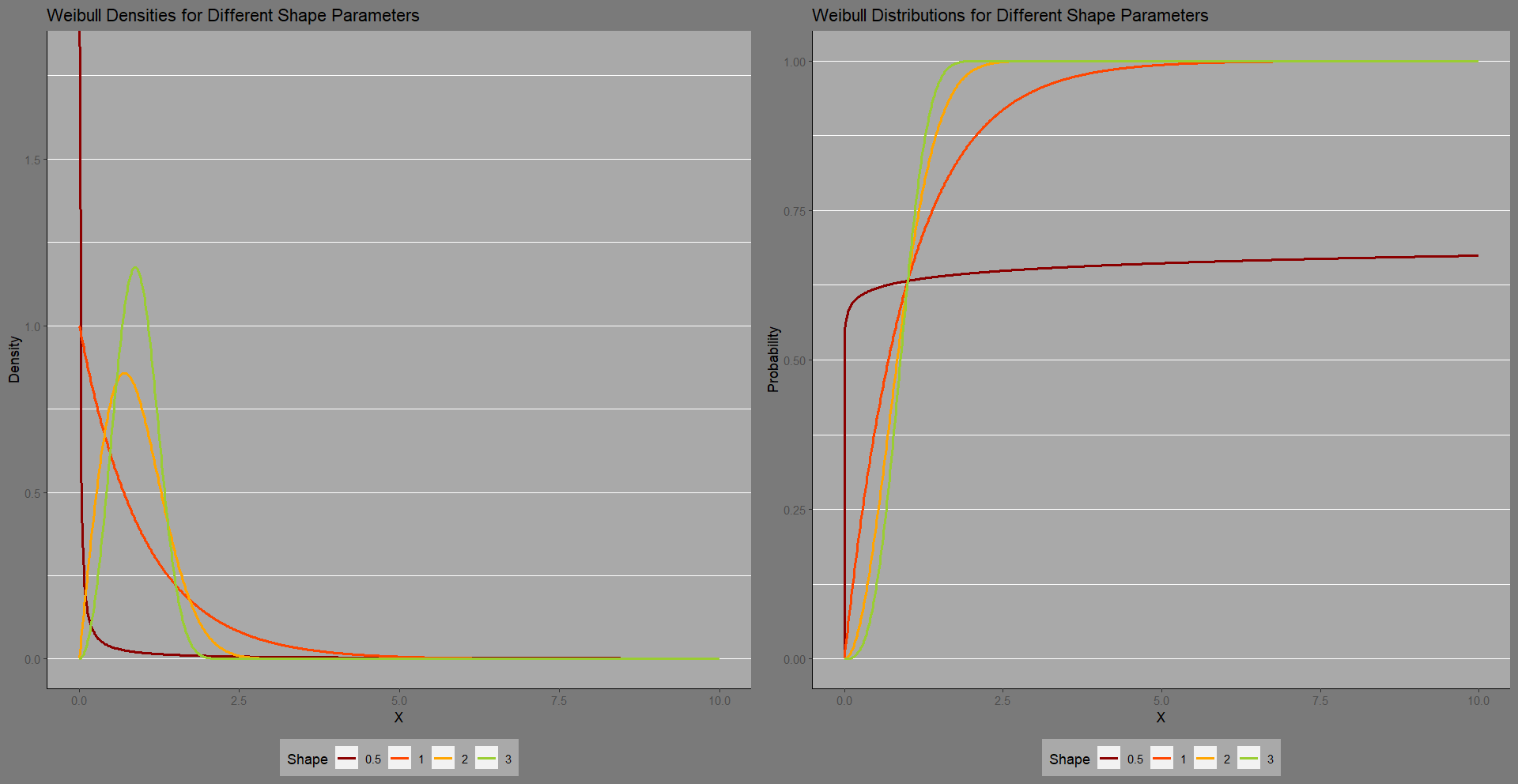

\[\frac{k}{\lambda}\left(\frac{x}{\lambda}\right)^{k-1}e^{-\left(\frac{x}{\lambda}\right)^k}\]Below the density and distribution functions are depicted for four Weibull distributions, where the scale parameters \(\lambda\) are set to \(1\) and the shape parameters are varied. Note that some sources also add a location shift to move the distribution left or right, here only two parameter Weibulls are depicted.

The shape parameter \(k\) has an important interpretation in terms of the failure rate. When \(k<1\), there is an immediate spike in failure, followed by a long haul, gradual failures over time. After the early failures, likely due to faulty manufacturing, failure rates decrease with time. When \(k=1\), the rate of failure is constant over time. This can be indicative that failures are being driven by external circumstances. Consistent external pressures on components cause a sustained, constant rate of failure. When \(k>1\), the failure rate increases with time. This may indicate that initial manufacturing quality is robust, but over time repeated stressors and accumulated damage aggregate to cause increasing failures.

While the Weibull distribution is robust and versatile, it has its limits. One of the criticisms of the Weibull is that it cannot accommodate “bathtub” failure patterns. The “bathtub” signal is a known pattern in failure modeling corresponding to the scenario where failures are increased both early and late in a products lifecycle. The early failures may be attributed to faulty manufacturing processes and the later failures to accumulated component damage. In 1993, Mudholkar and Srivastava published an expanded version of the Weibull, the exponentiated Weibull distribution, that can model bathtub failure patterns (Mudholkar & Srivastava 1993). The distribution adds another parameter \(\alpha\):

\[\alpha\frac{k}{\lambda}\left(\frac{x}{\lambda}\right)^{k-1}\left(1-e^{-\left(\frac{x}{\lambda}\right)^k}\right)^{\alpha-1}e^{-\left(\frac{x}{\lambda}\right)^k}\]For this project, the Weibull generally performed well in modeling cumulative failure patterns across different combinations of product family and client. There were a few combinations of customer and product family where the Weibull performed somewhat poorly. A closer look at these combinations revealed the failure data was more volatile than the other cases, and there were several change points in the failure patterns of these combinations. In particular, for these cases, the pandemic shutdown era appeared to have a more profound impact on the failure patterns than for other cases. To address these cases a more complex modeling framework and/or separation of data across change points (and possibly covariates) is required.